Despite an enormous variety of denominational (and non-denominational) bodies, there is remarkable unity around the praying of the Lord’s Prayer. Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants of all stripes pray this prayer and the prayer is prayed nearly verbatim in all traditions…except for the “forgive us our…” section of the prayer.

Despite an enormous variety of denominational (and non-denominational) bodies, there is remarkable unity around the praying of the Lord’s Prayer. Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants of all stripes pray this prayer and the prayer is prayed nearly verbatim in all traditions…except for the “forgive us our…” section of the prayer.

For some it is “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” For others it is “Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.” For still others it is “Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us.” I’ve often been asked, “Hey…how’s come?”

I grew up in the “sin/sin against us” context of the United Methodist Church. I teach at an Anglican seminary where we pray each morning in the “trespass/trespass against us” form. I pastor a Presbyterian congregation where we pray the prayer using “debts/debtors.” Sometimes I forget where I am and pray the prayer in the wrong way (it helps keep a fella humble). Why this variety? Who’s right? Well…in some ways, they all are.

Matthew presents Jesus petition like this: Matthew 6:12 12 Forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. Debts and debtors. This is a very literal translation of the Greek noun ophelēmata (“debts”) and ophelētais (“debtors”). The terms mean in Greek what they mean in English: financial obligations and the people who owe them.

Clearly Jesus is using a metaphor from the marketplace. We all understand financial obligations (some of us all too well!), and we can understand financial obligations as a metaphor representing sin. We need God to forgive our debts not because we are his debtors in any financial sense; we owe him rather perfect obedience and righteousness which we don’t fulfill. We’re sinners. And we are to forgive our debtors, that is to say, metaphorically, those who sin against us. This is all quite obvious if we compare the Parable of the Unmerciful Servant (Matthew 18:21-35). There Jesus uses financial obligation again as a vivid picture of our sin. It works well too with the notion of forgiveness. Debts can be forgiven, and forgiveness of sin is what we seek from God. Debt=sin.

In Luke’s gospel Jesus puts it this way: Luke 11:4 NIV84 4 Forgive us our sins, for we also forgive everyone who sins against us. So, “sin/sin against us” the NIV 1984 translates. The ESV reads a little differently: Luke 11:4 ESV 4 and forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive everyone who is indebted to us. Here “sins/those indebted to us.” Why the difference in translation? The Greek literally says “sin” in the first half of the verse, and “to the one who owes us” (opheilonti – a sister of the “debt” forms discussed above) in the second half of the verse. Luke is making explicit what is implicit in Matthew. When Jesus talks about forgiving “debts” he means forgiving “sins.” The debts he’s talking about are sin debts. We need to be forgiven our sins by God and we need to forgive others their sins against us.

So, “debts/debtors” pray-ers pray the prayer in the form presented in Matthew, preserving the debts-for-sin metaphor; the “sin/sin against us” pray-ers pray the prayer in a form closer to that preserved in Luke’s gospel, making the metaphor of debts=sins explicit.

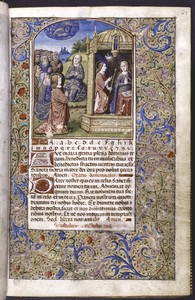

So where did “trespasses/trespass against us” come from? This is a hard question to answer in some ways. It is rather puzzling because it is the most widespread traditional English version of the prayer, but it doesn’t really reflect the biblical wording of the prayer in either gospel. It showed up in the Greek versions of the prayer in the 3rd century author Origen of Alexandria (the Greek term is paraptōmata). This wording made its way into important English translations such as the 1549 Book of Common Prayer.

Where did it come from in the first place if not from the prayer of Jesus as presented by Matthew and Luke? The most likely explanation is that it comes from the mention of “trespasses” in the context immediately following the prayer in Matthew’s gospel.

Jesus follows up the prayer with this teaching on forgiveness: Matthew 6:14-15 NIV 14 For if you forgive men when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. 15 But if you do not forgive men their sins, your Father will not forgive your sins. The term for “sins” used here? Technically it is “trespasses” (paraptōmata). Matthew 6:14-15 ESV 14 For if you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you, 15 but if you do not forgive others their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.

So Jesus here uses yet another metaphor for sin. Now it is not a financial metaphor, but a property one. “Trespassing” – an illegal violation of a boundary, crossing a limit. To trespass is to violate a boundary, to transgress the Law of God. It is a picture of sin. The NIV translates out the metaphor, making it simply “sins.”

So, what seems to have happened is that the church fathers (later followed by some important English translators) imposed Jesus’ property metaphor (“trespasses”) back onto the Lord’s Prayer in place of the financial metaphor (“debts”). Why did they do this? It is difficult to say. My personal theory is that they like the word “trespass” because it relates to a familiar Old Testament metaphor of sin. Sin is often pictured in the OT using the Hebrew verb gah-var – to transgress (or trespass). They chose the more common metaphor across the whole of scripture.

One of my favorite things to do at a funeral is to pray the Lord’s Prayer. It is an interesting occasion which often brings together a disparate group of people, including folks from many different Christian traditions. I always offer the preamble, “We Presbyterians pray using ‘debts/debtors,’ but you pray the prayer however you know it.” I love the cacophony that follows when we reach that petition. It is beautiful picture of unity in our common faith despite minor differences.

Debts, transgressions, sins. Whatever word or metaphor we use, we’ve all got them before a holy God. And they need to be forgiven.